BY: NICOLE SCHMIDT

It’s late. The sun had dipped behind the buildings of the London Ontario skyline hours ago and a dimly lit moon is suspended in its place. Illuminated by nothing but the faint glow of the sky, the sidewalks below appear to be unusually empty. There are street lamps on each block but they fail to emit any source of light, leaving the city immersed in darkness.

She wanders down a secluded side street, glancing behind her with every few steps she takes. The darkness conceals the shadows, disguising any form of life hidden within it. She starts walking faster. The feeling of fear overpowers her ability to think clearly, to breathe steadily. With another glimpse over her shoulder, she sees him —a faceless man dressed in black pants and a black hoodie following closely behind her. She walks faster, but he continues to follow. She starts to run, but he catches up. There’s no one around—no one to hear her scream, no one to come to her rescue. Just darkness.

She wakes up in the safety of her bedroom. The faceless man has appeared in her nightmares too many times to count. It always ends the same way, leaving her feeling frightened and alone. She doesn’t know it yet, but in the apartment adjacent to hers lives a moderately overweight Asian man in his mid-twenties. He stares out his window into hers every day. As she looks at the ceiling of her bedroom, she can’t help but wonder when it’s going to end. When she’ll be able to wake up from this nightmare for good.

It all started in August 2013 on what appeared to be a pretty typical summer day. Kaitlin Narciso, now 20-years-old, was spending the weekend at her family’s cottage up north—something she did regularly. She was out for a hike accompanied by friends when she received a distraught phone call from her cousin, Nicole. “Kaitlin, you have a fake profile on Facebook. Someone is pretending to be you.”

To any one of Kim Lake’s dozens of Facebook friends, she looked like someone who stayed in shape and had a wide circle of friends. She was petite, just hitting the five-foot mark, and wore a size two. Her posts showed that she had been to Jamaica and dressed up as a Police Officer for Halloween.

But what each one of Lake’s “friends” probably didn’t know was that the photos appearing on their newsfeeds, the ones that they “liked” and posted vulgar comments on, weren’t of Kim Lake. They were of Kaitlin Narciso.

Lake’s profile had been active for roughly three years before Narciso became aware of it. It contained photos dating back to high school and was updated every time she posted something to her own account. “You’re looking at your photos, everything that is you, but it isn’t because this person created an entire illusion,” says Narciso. “[At the time] I was thinking, ‘you know what, it could be worse.’ And it did get worse.”

Facebook has over 1.23 billion monthly active users. According to Facebook, between 5 and 6 per cent (or roughly 68 million—97 per cent of which are registered as females) are fake accounts.

Currently, Facebook has no substantial countermeasures in place to prevent individuals from entering fake data. This means that anyone has the ability to create a profile in your name, using your photos, without your knowledge—and it happens every day. It’s as simple as logging onto the site, searching for a new victim, copying their photos to their desktop and then re-uploading them to a new account. It takes 10 minutes to do, but can take months to have removed.

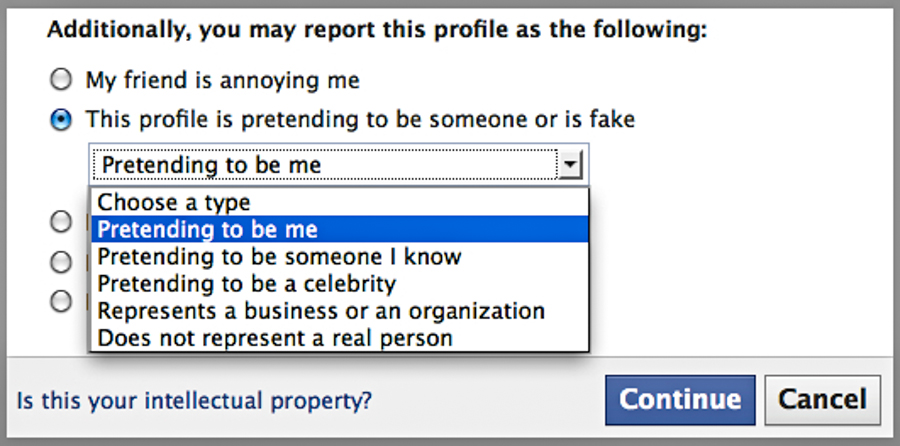

Stealing someone’s identity on social media is a faceless crime—one that often has no consequences for the impersonator. In 2012, Facebook initiated a system that gave users the opportunity to report fake accounts in hopes of strengthening their methods of detecting and eliminating these profiles. The terms and conditions condemn accounts that pretend to be someone else, use someone else’s photos, list a fake name, or don’t represent a real person. Yet when these terms and conditions are violated the onus falls on the user to handle the problem.

To report a fake account, a user must answer several questions regarding the profile, including the problem at hand and what the user is doing. If the answers selected violate the community standards, the user becomes eligible to submit the profile to Facebook for review. But with the increasing number of site users, it has become difficult for Facebook to keep up with the amount of complaints received. The result? Anyone who finds themselves dealing with a case of online identity theft could end up on a long wait list.

Twenty-year-old Kelsey MacPhee had ongoing issues with fake accounts. The first account she came across wasn’t by chance—the profile had added her as a friend and proceeded to send her messages, claiming that she was the “real Kelsey” and accusing her of being an imposter. Several fake profiles have been created in her name over the past six years and reporting them yielded no results. She has since given up on trying to get them taken down.

Currently, Facebook has no substantial countermeasures in place to prevent individuals from entering fake data. This means that anyone has the ability to create a profile in your name, using your photos, without your knowledge—and it happens every day.

Faith Lush encountered a similar situation a few years back when she was in high school. Someone had created a fake account in her name and then added her as a friend. Whoever was behind the screen was impersonating her by sending messages to people on her friends list. It took months for the profile to be removed. Then, in her first year of college, another fake account was created—it’s still active today.

Narciso found herself stuck on the same waiting list. Having filed several reports to Facebook without any result, she tried to deal with the problem directly by sending Lake a message from her mom’s account saying, “If you don’t take this profile down, we will contact the police.” The reply, sent through Instagram messenger (a service that doesn’t allow a user to permanently log a message), contained a photo of a handgun placed on a chair with the accompanying text, “You’ll contact the police is complete bullshit. She better be careful.”

Despite the threats warning her not to, Narciso contacted the police several times—which proved to be useless. They told her that unless something physically happened to her, there was nothing they could do.

Gail Regan, a detective with the Toronto Police, says that if a complaint is received, no matter what the level of seriousness is, an investigation will take place only once the case of identity theft is confirmed. The Toronto Police have a contact at Facebook Canada to help move investigations along. But still, tracking down the culprits can be a difficult process. Police must obtain a warrant—something that can take weeks, even months to get signed and approved in court. Even with a warrant, the possibilities in cyberspace appear to be infinitely greater. A person has the ability to disguise their Internet protocol (IP) address, a unique set of numbers assigned to each computer or device that functions to network interface identification and location addressing, to make it appear as though they’re in a different country. Tracking these users becomes incredibly tedious and finding the time to catch each and every Facebook impersonator seems unrealistic.

Proxies allow Facebook impersonators the ability to disguise their IP address to make it appear as though they are in a different country. Tracking fake users becomes incredibly tedious and finding time to catch everyone is unrealistic.

Gil Zvulony, a Toronto Internet lawyer, says that based on his experiences, people who fall victim to these sorts of crimes often go to the police, only to be told that it’s a civil matter and they should go see a lawyer.

“Police are not taking these cases very seriously … these cases are having a much more devastating effect on someone than if their car gets broken into, or somebody steals their bike,” says Zvulony. “You have situations where these things happen often and these people get away with it.”

Handling the case in court isn’t always a realistic option. The victim is left to fund the lawsuit by themselves, which can be quite expensive. Not only that, but Zvulony says that this type of thing is relatively new for the court system, so judges are often in need of guidance. It’s not that the concept of identity theft is new, it’s the fact that there are new ways to commit the crime that have made applying existing laws more difficult.

*Zachary Adkins created a fake Facebook account and from there, several online dating profiles because he knew that the consequences would be non-existent. The idea stemmed from a desire to help out his socially awkward and non-flirtatious roommate who wanted to learn how to talk to girls. By generating an alter-identity online, he was able to see how guys interact with girls from the alternative perspective.

The photos were stolen off of a Reddit thread called “safe for work redheads”—a collection of sexually suggestive images from redheaded women that, ironically, were not safe for work. Adkins said he chose one at random and, being a fan of alliteration, named her Sarah Syncretic—an art history major at the University of Toronto. He and his friend began harassing guys who would send Sarah messages, drilling them about their sex lives. On a few occasions, he would even send admirers to random locations, claiming that Sarah would meet them there.

Within a matter of months, the profile had over 500 Facebook friends. She was especially popular with men in Iowa, according to Adkins. He explained that the odds of getting caught are almost non-existent, seeing as he knows serious action is never taken unless the case is severe enough. But even then, Adkins says that by using a proxy server, the odds of being found are unlikely.

Proxy servers are used primarily by corporations and act as an intermediary between a web browser and the Internet. When used, proxies can conceal or convert an IP address, making tracking a device incredibly difficult. “It takes an extensive amount of work to find out who an individual is … I don’t think anyone has the patience,” Adkins says.

Handling the case in court isn’t always a realistic option. The victim is left to fund the lawsuit by themselves. It’s not that the concept of identity theft is new, it’s the fact that there are new ways to commit the crime that have made applying existing laws more difficult.

In past years, new bills have been introduced to parliament requesting amendment of laws surrounding identity theft, but the majority of them rarely make it past a second reading. The most recent proposal, brought forth on March 10, 2010, died after its first reading. Tony Verbora, a third year doctoral student at the University of Ottawa working on research relating to the lived experience of identity theft victimization in Canada, says that this could be due to the fact that although identity theft is an offence under the Criminal Code of Canada, there is no concrete definition of what it is.

“No one can steal your identity because your identity is you. It’s a part of you. All they can do is impersonate you…your identity in the criminal code is talked about biological, DNA, retina display, all those kinds of things,” says Verbora.

It had been three months since the profile was first discovered. Narciso had gone through the process of filling out countless online forms and, in a desperate attempt to finally have the account removed, she wrote a letter and mailed it to Facebook headquarters. Still, no progress was being made. She came back to her apartment one night to find that her new roommate, who she describes as a “narcissistic habitual drug addict,” had thrown a party. Upon retreating to her bed to watch an episode of Gilmore Girls, she realized that someone had been in her room and taken her laptop.

It started with a phone call—a whisper of her name on the other end of the line, and then silence. From there, a text message from an unknown number saying, “I have your laptop. If you ever want your Gilmore Girls DVD back, let me know.” Day after day, her phone would ring. A faceless man on the other end of the line would threaten her with sexual assault, yelling vulgar things about “wanting to shove his 13 inch cock inside of her.”

Another trip to the police station yielded the same results. Again, she was told that there wasn’t much they could do.

Five months had passed. By this point, both of Narciso’s roommates had moved out, leaving her by herself and feeling more alone than ever. She recalls days where she would sit in her bed for hours not wanting to do anything or talk to anyone. She rarely slept through the night, if at all.

“There were times where I would breakdown, I just wasn’t myself. No one could really talk to me. Every time someone tried … I would snap or just be on edge. Every time I was alone on the street, I’d be watching my back,” says Narciso.

The psychological effects of being a victim of identity theft can, in most cases, be the most damaging. Verbora says that a lot of times, people can experience what he refers to as “double victimization.” They are victims to begin with and when they go to court or the police, they feel like no one is reacting to the situation—despite them fearing for their life.

The psychological effects of being a victim of identity theft can, in most cases, be the most damaging. Often times, people can experience what he refers to as “double victimization”: they feel like no one is reacting to the situation—despite them fearing for their life.

Photo by DailyHerald/BrianHill

Karen Abrams, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto who specializes in the consequences of stalking, says that victims can experience a wide range of both psychological and occupational consequences. Some people suffer from anxiety, depression, panic attacks and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) while others must take time off of work or spend a lot of money on security measures. At a recent doctor’s appointment, Narciso’s physician diagnosed her with PTSD—a mental illness that is most common among war veterans.

Although it can be difficult to determine the exact motivation behind stealing someone’s identity online, Abrams says that people’s actions can be driven by feelings of rejection, resentment, boredom or dissatisfaction with their own lives.

Progress had finally been made after a private investigator began working on Narciso’s case. Police had managed to track down and arrest the person who had stolen the laptop—a moderately overweight Asian man in his mid twenties. He lived in the apartment adjacent to Narciso’s and stared out his window into hers every day. After the arrest was made and charges were pending, the user—not Facebook—had finally removed the profile.

A Facebook privacy glitch a few years back set all private profiles to public. Users needed to manually adjust the settings in order to fix the problem. On January 1, 2015, Facebook updated their terms and policies. Users no longer have the option to keep their profiles out of public search, which means anyone can access a person’s basic information, such as gender, along with profile pictures and cover photos.

For Narciso, it seemed as though life was finally getting back to normal after nearly a year of living in what she describes as a horror movie. In attempts to find a former co-worker and good friend, Narciso’s mom was searching for someone named “Pat.” Within the list of suggested profiles was someone named “Pat Hope.” Upon clicking the name, photos of Narciso flooded the page. Kim Lake had reactivated the profile, but under a different name. After getting in contact with the police yet again, they told her that her stalker had been released. The case wasn’t strong enough because there was no physical harm, so no prosecution could be made. For the time being, Narciso continues to play the waiting game.

Though she refrains from using Facebook and other social media sites to the extent she did prior to the incident, she says that in an odd, twisted way, Kim Lake helped her define herself as an individual. “You realize façades are easy to manipulate, to create, to fabricate. But what’s the point of being fake? I’d be doing exactly what Kim Lake did to me to myself.”

Pat Hope’s profile has since been removed and to her knowledge, Kim Lake no longer exists. Her stalker still lives in London, but is required to keep his distance.

“You never know when it’s actually over. Or if it’s over. From what I hope, there’s no more of me.”

*Some names have been changed to protect anonymity

Sources: cnbc.com, w3bsecurity.com, theglobeandmail.ca, itproportal.com, rajeshrana.net, dailyherald.com, wired.de